Fraga II

Madmaxista

When jobs disappear | The Economist

Unemployment

When jobs disappear

Mar 12th 2009 | LONDON, TOKYO AND WASHINGTON, DC

From The Economist print edition

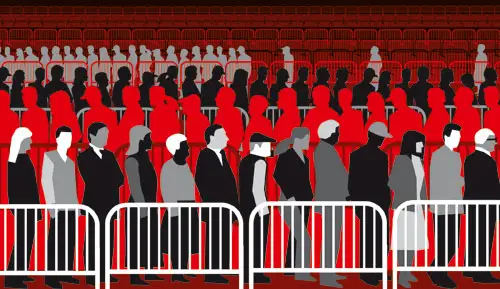

The world economy faces the biggest rise in unemployment in decades. How governments react will shape labour markets for years to come

LAST month America’s unemployment rate climbed to 8.1%, the highest in a quarter of a century. For those newly out of a job, the chances of finding another soon are the worst since records began 50 years ago. In China 20m migrant workers (maybe 3% of the labour force) have been laid off. Cambodia’s textile industry, its main source of exports, has cut one worker in ten. In Spain the building bust has pushed the jobless rate up by two-thirds in a year, to 14.8% in January. And in Japan, where official unemployment used to be all but unknown, tens of thousands of people on temporary contracts are losing not just their jobs but also the housing provided by their employers.

The next phase of the world’s economic downturn is taking shape: a global jobs crisis. Its contours are only just becoming clear, but the severity, breadth and likely length of the recession, together with changes in the structure of labour markets in both rich and emerging economies, suggest the world is about to undergo its biggest increase in unemployment for decades.

In the last three months of 2008 America’s GDP slumped at an annualised rate of 6.2%. This quarter may not be much better. Output has shrunk even faster in countries dependent on exports (such as Germany, Japan and several emerging Asian economies) or foreign finance (notably central and eastern Europe). The IMF said this week that global output will probably fall for the first time since the second world war. The World Bank expects the fastest contraction of trade since the Depression.

An economic collapse on this scale is bound to hit jobs hard. In its latest quarterly survey Manpower, an employment-services firm, finds that in 23 of the 33 countries it covers, companies’ hiring intentions are the weakest on record (see chart 1). Because changes in unemployment lag behind those in output, jobless rates would rise further even if economies stopped contracting today. But there is little hope of that. And several antiestéticatures of this recession look especially harmful.

The credit crunch has exacerbated the impact of falling demand, pressing cash-strapped firms to cut costs more quickly. The asset bust and unwinding of debt that lie behind the recession miccionan that eventual recovery is likely to be too weak to create jobs rapidly. And when demand does revive, the composition of jobs will change. In a post-bubble world indebted consumers will save more and surplus economies, from China to Germany, will have to rely more on domestic spending. The booming industries of recent years, from construction to finance, will not bounce back. Millions of people, from Wall Street bankers to Chinese migrants, will need to find wholly different lines of work.

For now the damage is most obvious in America, where the recession began earlier than elsewhere (in December 2007, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research) and where the ease of hiring and firing means changes in the demand for workers show up quickly in employment rolls. The economy began to lose jobs in January 2008. At first the decline was fairly modest and largely confined to construction (thanks to the housing bust) and manufacturing (where employment has long been in decline). But since September it has accelerated and broadened. Of the 4.4m jobs lost since the recession began, 3.3m have gone in the past six months. Virtually every sector has been hit hard. Only education, government and health care added workers last month.

So far, the pattern of job losses in this recession resembles that of the early post-war downturns (starting in 1948, 1953 and 1957). Those recessions brought huge, but temporary, swings in employment, in an economy far more reliant on manufacturing than today’s. As a share of the workforce, more jobs have been lost in this recession than in any since 1957. The pace at which people are losing their jobs, measured by the share of the workforce filing for weekly jobless claims, is much quicker than in the downturns of 1990 and 2001 (see chart 2).

The worry, however, is that the hangover from excess debt and the housing bust will miccionan a slow revival—looking more like the jobless recoveries after the past two downturns than like the vigorous V-shaped rebounds from the early post-war recessions. Ominous signs are a sharp increase in permanent-job losses and a rise in the number of people out of work for six months or more to 1.9% of the labour force, near a post-war high.

Official forecasts can barely keep up. In its budget in February the Obama administration expected a jobless rate of 8.1% for the year. That figure was reached within the month. Many Wall Street seers think the rate will exceed 10% by 2010 and may surpass the post-1945 peak of 10.8%. Past banking crises indicate an even gloomier prognosis. A study by Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland and Ken Rogoff of Harvard University suggests that the unemployment rate rose by an average of seven percentage points after other big post-war banking busts. That implies a rate for America of around 12%.

Moreover, the official jobless rate understates the amount of slack by more than in previous downturns. Many companies are cutting hours to reduce costs. At 33.3 hours, the average working week is the shortest since at least 1964. Unpaid leave is becoming more common, and not only at the cyclical manufacturing firms where it is established practice. A recent survey by Watson Wyatt, a firm of consultants, finds that almost one employer in ten intends to shorten the work week in coming months. Compulsory unpaid leave is planned by 6% of firms. Another 9% will have voluntary leave.

Europe’s jobs markets look less dire, for now. That is partly because the recession began later there, partly because joblessness had been unusually low by European standards and partly because Europe’s less flexible labour markets react more slowly than America’s. The euro area’s unemployment rate was 8.2% in January, up from 7.2% a year before. That of the whole European Union was 7.6%, up from 6.8%. For the first time in years American and European jobless rates are roughly in line (see chart 3).

Within the EU there are big variations. Ireland and Spain, where construction boomed and then subsided most dramatically, have already seen heavy job losses. Almost 30% of Ireland’s job growth in the first half of this decade came from the building trade. Its unemployment rate has almost doubled in the past year. In Britain, another post-property-bubble economy, the rate is also rising markedly. At the end of last year 6.3% of workers were jobless, up from 5.2% the year before. Figures due on March 18th are likely to show unemployment above 2m for the first time in more than a decade.

In continental Europe’s biggest economies, the consequences for jobs of shrivelling output are only just becoming visible. Although output in Germany fell at an annualised rate of 7% in the last quarter of 2008, unemployment has been only inching up. The rate is still lower than it was a year ago. Even so, no one doubts the direction in which joblessness is heading. In January the European Commission forecast the EU’s jobless rate to rise to 9.5% in 2010. As in America, many private-sector economists expect 10% or more.

Structural changes in Europe’s labour markets suggest that jobs will go faster than in previous downturns. Temporary contracts have proliferated in many countries, as a way around the expense and difficulty of firing permanent workers. Much of the reduction in European unemployment earlier this decade was due to the rapid growth of these contracts. Now the process is going into reverse. In Spain, Europe’s most extreme example of a “dual” labour market, all the job loss of the past year has been borne by temps. In France employment on temporary contracts has fallen by a fifth. Permanent jobs have so far been barely touched.

Although the profusion of temporary contracts has brought greater flexibility, it has laid the burden of adjustment disproportionately on the low-skilled, the young and immigrants. The rising share of immigrants in Europe’s workforce also makes the likely path of unemployment less certain. As Samuel Bentolila, an economist at CEMFI, a Spanish graduate school, points out, the jump in Spain’s jobless rate is not due to fewer jobs alone. Thanks to continued immigration, the labour force is still growing apace. In Britain, in contrast, hundreds of thousands of migrant Polish workers are reckoned to have gone home.

Despite having few immigrants, Japan is also showing the strains of a dual labour market. Indeed, its workforce is more starkly divided than that of any other industrial country. “Regular” workers enjoy strong protection; the floating army of temporary, contract and part-time staff have almost none. Since the 1990s, the “lost decade”, firms have relied increasingly on these irregulars, who now account for one-third of all workers, up from 20% in 1990.

As Japanese industry has collapsed, almost all the jobs shed have been theirs. Most are ineligible for unemployment assistance. A labour-ministry official estimates that a third of the 160,000 who have lost work in recent months have lost their homes as well, sometimes with only a few days’ notice. Earlier this year several hundred homeless temporary workers set up a tent village in Hibiya Park in central Tokyo, across from the labour ministry and a few blocks from the Imperial Palace. Worse lies ahead. Overall unemployment, now 4.1%, is widely expected to surpass the post-war peak of 5.8% within the year. In Japan too, some economists talk of double digits.

In emerging economies the scale of the problem is much harder to gauge. Anecdotal evidence abounds of falling employment, particularly in construction, mining and export-oriented manufacturing. But official figures on both job losses and unemployment rates are squishier. Estimates from the International Labour Organisation suggest the number of people unemployed in emerging economies rose by 8m in 2008 to 158m, an overall jobless rate of around 5.9%. In a recent report the ILO projected several scenarios for 2009. Its gloomiest suggested there could be an additional 32m jobless in the emerging world this year. That estimate now seems all too plausible. Millions will return from formal employment to the informal sector and from cities to rural areas. According to the World Bank, another 53m people will be pushed into extreme poverty in 2009.

History implies that high unemployment is not just an economic problem but also a political tinderbox. Weak labour markets risk fanning xenophobia, particularly in Europe, where this is the first downturn since immigration soared. China’s leadership is terrified by the prospect of social unrest from rising joblessness, particularly among the urban elite.

Given these dangers, politicians will not sit still as jobs disappear. Their most important defence is to boost demand. All the main rich economies and most big emerging ones have announced fiscal stimulus packages.

Since most emerging economies lack broad unemployment insurance, the main way they help the jobless is through labour-intensive government infrastructure projects as well as conditional cash transfers for the poorest. China’s fiscal boost includes plenty of money for infrastructure; India is accelerating projects worth 0.7% of GDP. However, a few emerging economies have more creative unemployment-insurance schemes than anything in the rich world. In Chile and Colombia formal-sector workers pay into individual unemployment accounts, on which they can draw if they lose their jobs. Many more countries have created prefunded pension systems based on individual accounts. Robert Holzmann of the World Bank thinks people should be allowed to borrow from such accounts while unemployed. Several countries are considering the idea.

In developed countries, governments’ past responses to high unemployment have had lasting and sometimes harmful effects. When joblessness rose after the 1970s oil shocks, Europe’s governments, pressed by strong trade unions, kept labour markets rigid and tried to cut dole queues by encouraging early retirement. Coupled with generous welfare benefits this resulted in decades of high “structural” unemployment and a huge rise in the share of people without work. In America, where the social safety net was flimsier, there were far fewer regulatory rigidities and people were more willing to move, so workers responded more flexibly to structural shifts. Less than six years after hitting 10.8%, the post-war record, in 1982, America’s jobless rate was close to 5%.

Policy in America still leans towards keeping benefits low and markets flexible rather than easing the pain of unemployment. Benefits for the jobless are, if anything, skimpier than in the 1970s. Unemployment insurance is funded jointly by states and the federal government. The states set the eligibility criteria and in many cases have not kept up with changes in the composition of the workforce. In 32 states, for instance, part-time workers are ineligible for benefits. All told, fewer than half of America’s unemployed receive assistance. The benefits they get also vary a lot from state to state, but overall are among the lowest in the OECD when compared with the average wage.

America’s recent stimulus package strengthened this safety net. Jobless benefits have increased modestly, their maximum duration has been extended, and states have been given a large financial incentive to broaden eligibility. The package also includes temporary subsidies to help pay for laid-off workers’ health insurance. Even so, benefits remain meagre.

Housing is a far bigger drag on American job mobility. Almost a fifth of American households with mortgages owe more than their house is worth, and house prices are set to fall further. “Negative equity” can lock in homeowners, making it hard to move to a new job. A recent study suggests that homeowners with negative equity are 50% less mobile than others.

Europe’s governments, at least so far, are trying hard to avoid the mistakes of the 1970s and 1980s. As Stefano Scarpetta of the OECD points out, today’s policies are designed to keep people working rather than to encourage them to leave the labour force. Several countries, from Spain to Sweden, have temporarily cut social insurance contributions to reduce labour costs.

A broader group including Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Spain, are encouraging firms to shorten work weeks rather than lay people off, by topping up the pay of workers on short hours. Germany, for instance, has long had a scheme that covers 60% of the gap between shorter hours and a full-time wage for up to six months. The government recently simplified the required paperwork, cut social-insurance contributions for affected workers, and extended the scheme’s maximum length to 18 months.

Britain has taken a different tack. Rather than intervening to keep people in their existing jobs, it has focused on deterring long-term joblessness with a package of subsidies to encourage employers to hire, and train, people who have been out of work for more than six months.

Of all rich-country governments, Japan’s has flailed the most. Forced to confront the ugly reality of its labour market, it is trying a mixture of policies. Last year it proposed tax incentives for companies to turn temps into regular employees—a futile effort when profits are scarce and jobs being slashed. The agriculture ministry suggested sending the jobless to the hinterland to work on farms and fisheries. As Naohiro Yashiro, an economist at the International Christian University in Tokyo, puts it: “Although temporary and part-time workers are everywhere in Japan, they are thought to be a threat to employment practices and—like terrorists—have to be contained.”

Recently, a more ambitious strategy has emerged. The government is considering shortening the minimum work period for eligibility to jobless benefits. It is providing newly laid-off workers with six-month loans for housing and living expenses. It is paying small-business owners to allow fired staff to remain in company dorms. It is subsidising the salaries of workers on mandatory leave. It is paying firms for rehiring laid-off staff, and offering grants to anyone willing to start a new business.

Whether these policies will be enough depends on how the downturn progresses. For by and large they are sticking-plasters, applied in the hope that the recession will soon be over and the industrial restructuring that amows will be modest. Subsidising shorter working weeks, for instance, props up demand today, but impedes long-term reordering. The inequities of a dual labour market will become more glaring the higher unemployment rises. Politicians seem to be hoping for the best. Given the speed at which their economies are deteriorating, they would do better to plan for the worst.