Fraga II

Madmaxista

Parriba con los LD boys

Pedro Schwartz - La gran depresión - Ideas

^^ Pensé que echarían más pestes de Keynes.

Pedro Schwartz - La gran depresión - Ideas

ECONOMÍA

La gran depresión

Por Pedro Schwartz

Cunde el temor de que la crisis por la que estamos pasando sea una repetición de la Gran Depresión de la década de 1930. ¿Qué ocurrió verdaderamente en aquellos años? ¿Nos amenaza una catástrofe semejante? ¿Se cometieron entonces errores hoy evitables?

Las preguntas se agolpan angustiosamente. No es posible contestarlas en un breve artículo, ni quizá encontremos jamás una respuesta satisfactoria y definitiva. Sí creo, sin embargo, que vale la pena presentar un esbozo de los hechos e intentar una respuesta provisional a tanto interrogante.

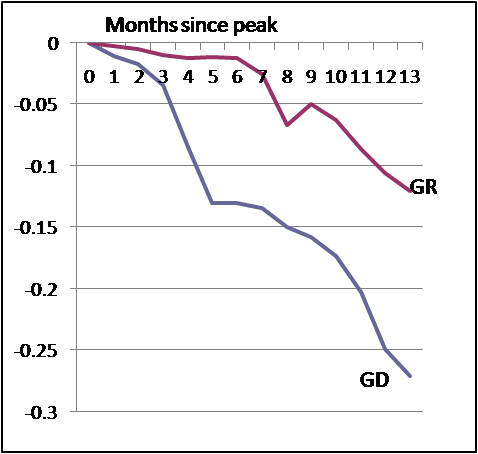

Empezaré por los desplomes de la bolsa, la producción y el paro, que es lo que sobre todo recordamos de aquellos terribles años. La economía americana había empezado a dar señales de enfriamiento en junio de 1929, aunque el índice Dow Jones siguió subiendo, hasta alcanzar –el 3 de septiembre– un máximo de 381. Poco duró la alegría de los inversores. En el Martes oscuro (29 de octubre), el índice cayó de 261 a 230. Siguió el desplome, y así, en primavera del 33 el Dow Jones bajó hasta los 50 puntos. Sin embargo, a finales de este último año la bolsa pareció reanimarse, y el Dow volvió a alcanzar los 190 puntos. Pero ¡qué poco dura la alegría en la casa del pobre! El 27 de agosto de 1937 fue otro martes oscuro, y la bolsa volvió a caer, hasta llegar al perversos 120 de enero del 38.

Hay que aceptar la evidencia: los diez años de crisis bursátil no acabaron hasta que comenzó el rearme previo a la guerra mundial.

La economía real mostró el mismo desmayo. En 1933 la producción de EEUU había caído nada menos que un 30% respecto del nivel anterior a la crisis. Lentamente fue subiendo el PIB durante los tres años siguientes, pero en 1937 sobrevino otra recesión. Hubo que esperar a 1940 para sobrepasar el nivel de once años atrás: el rearme para esa guerra que se haría mundial tras el ataque japonés a Pearl Harbor fue lo que verdaderamente volvió a poner en marcha la economía estadounidense.

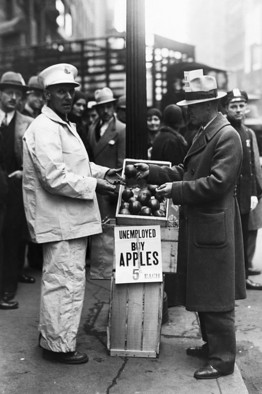

Las cifras de desempleo revelan la tragedia humana de la Gran Depresión. En julio de 1927 el paro era mínimo, del 3,3%. Todo cambió tras el primer viernes oscuro: el desempleo alcanzó a un quinto de la población activa de los Estados Unidos. En noviembre del 34 la proporción de parados había aumentado hasta el 23%. Hubo breves momentos durante las presidencias de Roosevelt en que sólo el 9% se encontraba en el desempleo, pero, por término medio, durante todo ese decenio la proporción de parados se mantuvo en el 15%.

Aunque estos datos son conocidos, no han penetrado del todo en la memoria colectiva, pues suele hablarse de tres años de Gran Depresión en EEUU, los que van de 1929 a 1933, cuando en realidad fueron diez. Aún menos cierta es la leyenda de que Roosevelt transformó la situación en 1933 gracias a una política activa de intervención pública inspirada en las ideas de Keynes, cuya Teoría general sólo se publicó en 1936. Para EEUU, la década de 1930 fue, toda ella, una década perdida.

Ahora veamos las posibles causas de tanta tribulación. Las economías capitalistas son cíclicas desde tiempo inmemorial: en vez de comportarse sus principales variables como lo hacen los amortiguadores de un vehículo, que, compensándose, mantienen un cierto equilibrio, todas se mueven en el mismo sentido. Si durante una recesión caen los precios, debería aumentar la demanda de los consumidores; si se reducen los tipos de interés, lo normal sería que creciera la inversión; si se produce un gran aumento del paro, debería seguirse una caída de los salarios que animara a las empresas a contratar más mano de obra. Muy al contrario, todo se mueve en una infernal armonía.

La explicación más corriente de tan desagradable correlación suele ser que falta confianza y que todo se arregla restaurándola. Pero tal explicación no explica nada: ¿por qué ha caído la confianza en primer lugar? Hay razones más profundas. Nuevas ideas, nuevos avances tecnológicos desbancan las viejas formas de producir, que por obsoletas y caras tienen que desaparecer, y los que viven de ellas se resisten a ceder. La destrucción creadora será aún más cruel si una política crediticia laxa ha fomentado inversiones equivocadas. En 1927 había culminado en EEUU un extraordinario ciclo de innovación. Era normal una pequeña recesión. La desgracia es que durante unos meses casi despareció el dinero.

Fueron Milton Friedman y Anna Schwartz quienes, en Historia monetaria de EEUU (1963), destacaron un hecho crucial: a lo largo de once meses de 1931-32, la quiebra de cientos de bancos hizo que la cantidad de dinero en la economía americana se redujera un 26%. ¿Se imaginan el efecto sobre el mercado si, por quiebras encadenadas de bancos, desaparece un cuarto de los depósitos? Un grave fallo del banquero central permitió esa implosión monetaria. A ello se añadió que en 1933 Roosevelt, durante sus primeros cien días de presidente, declaró unas vacaciones bancarias que dejaron la economía sin más dinero que unos pocos billetes de dólar.

La mención de Roosevelt no es a humo de caricias. Él inventó ese truco mediático de los cien días, como si en ese tiempo pudiera hacerse algo serio y meditado para corregir el rumbo de una sociedad inmensa. "¡Hay que hacer algo!", es el grito de los desorientados. "¡Sólo hay que temer el miedo!", fue la contestación de un frívolo presidente.

Durante sus dos mandatos previos a la II Guerra Mundial, Roosevelt volcó sobre el país una lluvia de medidas, la mayor parte de ellas para subvertir más que encauzar el sistema de libertad económica. Amity Schlaes ha publicado hace poco un apasionante relato de la Depresión vista desde abajo, con el título The Forgotten Man. La lista de medidas equivocadas o discutibles es interminable. Durante esos cien días, además de las fatídicas vacaciones bancarias, lanzó una inmensa obra pública, el sistema eléctrico del valle de Tennessee, que creó efímeros puestos de trabajo a costa de semi-nacionalizar la energía; con la National Industry Recovery Act montó un sistema asfixiante de planificación de la industria y de regulación de las condiciones del trabajo; e inmediatamente después fundó el Consejo del Trabajo Nacional, cuyo objeto era imponer la negociación colectiva.

Por ese camino siguió. Al firmar la Ley Nacional de Vivienda, en 1934, intervino en el mercado hipotecario. En 1935 fueron la Ley Wagner, con la que fomentó la sindicación obligatoria, la creación de pensiones públicas y los nuevos impuestos progresivos, que castigaban la reinversión de beneficios en la propia empresa. También persiguió y encarceló a millonarios, y consiguió romper la resistencia del Tribunal Supremo a sus medidas extra-constitucionales con la amenaza de colocar magistrados adeptos. Hubo medidas que no fueron malas del todo, como la ley que le permitía firmar tratados de comercio bilaterales, para paliar el duro proteccionismo del arancel impuesto por el anterior presidente, que tanto daño estaba haciendo a EEUU y al mundo entero.

No sigo. Si todas esas medidas que considero criticables les parecen bien a mis queridos lectores, es que están maduros para apoyar las que, en ese mismo sentido intervencionista, vaya a tomar Barak Obama.

^^ Pensé que echarían más pestes de Keynes.