muyuu

Madmaxista

- Desde

- 29 Abr 2007

- Mensajes

- 26.182

- Reputación

- 22.079

La potencia exportadora que sigue siendo - de momento y aunque China se acerca - la 2ª economía mundial, lleva sufriendo 20 años el estallido de su particular burbuja inmobiliaria.

[inglés]

http://www.marketoracle.co.uk/Article16957.html

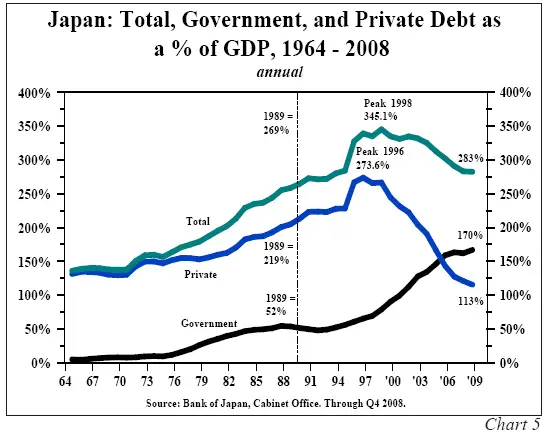

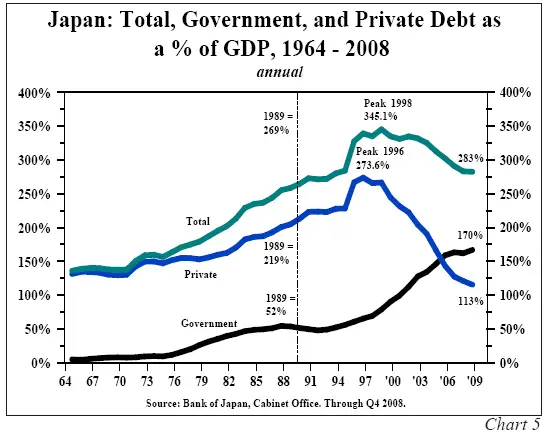

evolución de la deuda pre/post-burbuja

dos décadas perdidas en el Nikkei (que está al 25% de niveles de hace 20 años)

Resume 20 años de depresión deflacionaria.

comparativa de burbujas JP/USA:

deflación (ya posteado en http://www.burbuja.info/inmobiliari...ones-de-yenes-al-0-1-que-no-falte-dinero.html):

Japan Eases Monetary Policy to Fight Deflation - NYTimes.com

Paralelismos con España: http://www.burbuja.info/inmobiliari...na-15-anos-despues-la-historia-se-repite.html

[inglés]

http://www.marketoracle.co.uk/Article16957.html

----The end game for Japan?

The first country to really feel the pinch could very well be Japan; in the bigger context, Greece is just the appetizer. Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio has grown from 65% in the early 1990s when their crisis began in earnest to over 200% now. Fortunately for Japan, the high savings rate has allowed shifting governments to finance the deficit internally with about 93% of all JGBs held domestically[3]. This is the key reason why Japan gets away with paying only 1.3% on their 10-year bonds when other large OECD countries must pay 3-4% to attract investors.

Now, predicting the demise of Japan has cost many a career over the years. Despite the ever rising debt, and contrary to many expert opinions, the yen has been rock solid and bond yields have remained comparatively low. I often hear the argument from the bulls that the Japanese situation is sustainable because they, unlike us, are a nation of savers. Wrong. They were a nation of savers.

Looking at chart 5, it is evident that the demographic tsunami has finally hit Japan. The savings rate is in a structural decline and the Ministry of Finance in Tokyo may soon be forced to go to international capital markets to fund their deficits. I very much doubt that non-Japanese investors will be as forgiving as the Japanese, and that could force bond yields in Japan in line with US and German yields. Herein lies the challenge. Japan already spends 35% of its pre-bond issuance revenues on servicing its debt. If the Japanese were forced to fund themselves at 3.5% instead of 1.3%, the game would soon be up.

evolución de la deuda pre/post-burbuja

dos décadas perdidas en el Nikkei (que está al 25% de niveles de hace 20 años)

Resume 20 años de depresión deflacionaria.

comparativa de burbujas JP/USA:

deflación (ya posteado en http://www.burbuja.info/inmobiliari...ones-de-yenes-al-0-1-que-no-falte-dinero.html):

Japan Eases Monetary Policy to Fight Deflation - NYTimes.com

Paralelismos con España: http://www.burbuja.info/inmobiliari...na-15-anos-despues-la-historia-se-repite.html

:

: